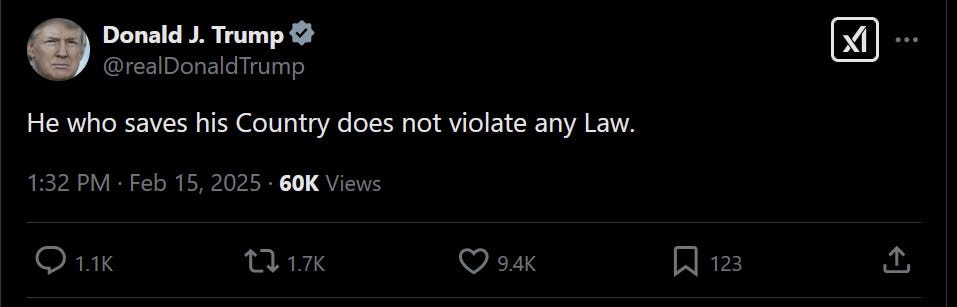

Today, the Schmittianism of the Trump administration was more or less avowed in this social media post by the president himself via this hackneyed version of a quote attributed to Napoleon:

What follows is something of a Schmitt 101 for those who need it, along with major prominent criticisms. In the last section, I fulfill the obligation of this Substack by bringing it back to the notion of the con—I’d guessing you’re thinking I can’t thread that needle, but it won’t prove difficult and, indeed, is necessary for what’s ahead.

Schmitt and Sovereignty

If I really missed something in writing The State of Sovereignty more than a decade ago, it’s that 1) I didn’t deal enough with modern sovereigntism and capitalism’s march, and 2) didn’t express clearly that Carl Schmitt's (1888 to 1985) was the bête noire of the whole damn thing—Schmitt was so obviously the sovereigntist one would have in mind that looking at it now, I see I didn’t even bother much to state that. The book is organized around confronting Schmitt’s Christian and transcendental (more simply: hierarchical) notion of sovereignty and modernity’s promise of a “pagan” form (the many gods the people would be under popular sovereignty), then caching out what remains of the idea of sovereignty for us today.

So, if you’re reading that Trump’s claim is “Schmittian” (or as a few wits put it on Bluesky: why “the Schmitt has hit the fan”) and wonder what that means, I’ll walk you through it here. Schmitt’s important because

His sovereigntism (if you’ve read or heard of Hobbes, he’s another “name” for this problem) is a constant threat to democracy

Both Bush II and the JD Vance wing of the Republican party have deep dived less through the writings of Schmitt than cartoon versions so they can sound more profound when pronouncing “because I said so.”

Many invocations of sovereignty or executive power today hearken back to Schmitt’s claim that the sovereign is he who is both within the law, while also the exceptional force that guarantees the law. Here’s Schmitt in an often quoted passage from his Political Theology: Four Chapters on the Concept of Sovereignty:

All significant concepts of the modern theory of the state are secularized theological concepts not only because of their historical development—in which they were transferred from theology to the theory of the state, whereby, for example, the omnipotent God became the omnipotent lawgiver—but also because of their systematic structure, the recognition of which is necessary for a sociological consideration of these concepts.

Carl Schmitt attests to this: the sovereign is exceptional to the law, just as God is to the laws of nature (after all, the Christian God performs supernatural miracles). This has a long lineage dating back to Jean Bodin, writing in the 16th century, and beyond. Here’s a key passage from Bodin, which I try to explain along the way in brackets:

Sovereignty is the absolute and supreme power over citizens and subjects of a commonwealth, which the Latins call maiestas [from which we get the word “majesty”]; the Greeks akra exousia [highest freedom to do as one pleases], kurion arche, and kurion politeuma [political sovereignty] . . . unlimited by time [and] not subject in any way to the commands of someone else [not your pesky judges or a legislative branch]. . . able to give laws to his subjects, and to suppress or repeal disadvantageous laws. . . . The laws of a sovereign prince, even if founded on good and strong reasons, depend solely on his own free will [so whether they are rational or not doesn’t matter—a key point in Bodin’s time since it means you can’t question the sovereign by saying he—always figured as masculine—is being irrational and thus could ’t have meant his edict, etc.]

Following from this framework, Schmitt draws a parallel between theological miracles (which transcend natural law) and sovereign power (which transcends political law)—now you see where Trump’s social media post today fits in. And if I’m quoting Bodin—famously an apologist for the divine right of kings—you should see how anyone who can read even a bit of history would see any of this is utterly foreign to the U.S. founding documents (and small-D democratic good sense).

For Schmitt, the sovereign's unique position emerges most clearly in times of crisis (i.e, when the sovereign is “sav[ing] the country”), when the normal constitutional order faces threats. The crucial point is that the sovereign alone determines what constitutes such a crisis—so no use in pointing out that the U.S. before a few weeks ago needed no darn saving, as Trump envisions it—and no pre-existing law can constrain this determination. This power to decide becomes the essence of sovereignty itself.

Now the advance, if one can call it that, of Schmitt over previous apologists for monarchism is that he weds this more clearly to a single decision that underlies the rest. And sovereignty is nothing other than this monopoly over this decision, which concerns the distinction between the political friend and enemy:

The political enemy is the other, the stranger; and it is sufficient for his nature that he is, in a specially intense way, existentially something different and alien, so that in the extreme case conflicts with him are possible [so not necessarily actual; we don’t have to be, say, at war]. These can neither be decided by a previous determined general norm nor by the judgment of a disinterested and neutral party.

This perspective forms the foundation of Schmitt's critique of liberalism. Where liberal theory envisions the state as a forum for consensus-building and measured compromise and tries to corral the executive within a Montesquieu-like mix of coequal branches of government, each with distinct powers. Schmitt contends that the state itself emerges from fundamental conflicts that forge political unity. The seemingly neutral administrative functions of the liberal state obscure this originary violence, and what’s more, all the rest falls away unless the sovereign has this power: since it’s the ultimate defender of the Constitutional order (via the military and police, etc.), you need him on that Wall; you want him on that Wall. As Schmitt argues:

Every legal order is based upon a decision... What is argued about is the concrete application, and that means who decides in a situation of conflict what constitutes the public interest or interest of the state, public safety and order, le salut public [French for public safety, but also a key term in French history dating to the Terror], and so on. The exception, which is not [indeed for Schmitt, cannot be] codified in the existing legal order, can at best be characterized as a case of extreme peril, a danger to the existence of the state, or the like. But it cannot be circumscribed factually and made to conform to a preformed law.

Thus, the sovereign's role is to determine when normalcy exists and when it has been suspended—making all law fundamentally situational in nature. That is, underneath it all, law is arbitrary since the normal order only exists insofar as the sovereign allows it. Hobbes’s claims in The Leviathan are very similar—he certainly allows for different forms of governance (tyranny, republics, etc.), but at the core of the political are sovereign acts and decisions that make the rest possible. The people serve the sovereign, not the other way around.

How Do We Argue With This?

This post arose in part from an exchange on Bluesky about Schmitt, with the claim made that the left needs to read and confront him. That's absolutely correct, but the "how" is crucial.

Simply dismissing Schmitt as a Nazi apologist (which he undoubtedly was) is insufficient since this “tendency” or “habit” or “threat” has always haunted the political. Within what I’ll call the academic left (but these debates have been more broad), we have seen the following moves against Schmittianism (though not of the left, for sure, I’ll include Strauss’s critique since the Claremont people sometimes shoo away their Schmittians via his work):

1. Schmitt = Nazi = Bad

The first is to dismiss him on account of his Nazism—and he was one; do not for a second believe any bad faith arguments among Claremont-type conservatives that he had some “internal migration”—he wanted to be the Nazi court jurist in the 1930s. For political reasons, he was eventually shunted aside, but saying he wasn’t really a Nazi because of that is like saying I don’t like baseball since the leagues didn’t pick me again this year.

(By using the word “dismiss,” I’m not myself dismissing this line of argument: being a Nazi is a great heuristic or shortcut to show that your political ideas are against the work of justice.)

2. Political Agonism

Another major move has been deconstructing the "friend/enemy" distinction. For example, Chantal Mouffe's approach has been to argue that a healthy democracy acknowledges conflict as inevitable, but channels it through democratic institutions. Instead of "enemies" to be destroyed, we have "adversaries" whose right to exist and hold opposing views is recognized. The goal is to transform antagonism into agonism—a vibrant, but ultimately contained, struggle within a shared democratic framework. This contrasts sharply with Schmitt's vision of a unified Volk defined by its opposition to an external (or internal) enemy.

Nevertheless, she doesn’t reject Schmitt; she applies him, and it’s worth pointing out that she’s not alone. Why work with this Nazi? Well, it happens that Schmitt’s critiques of Wiemar-era liberalism meets up well with left critiques of liberalism as all discussion, no action when it comes to what is decisive, and that it’s facing a permanent crisis of legitimacy in not answering to the needs of the political. (Insert any screaming you’ve done about Congressional Dems the last few weeks and you’re almost there.)

3. Giorgio Agamben

Giorgio Agamben is another major thinker to take up Schmitt—indeed, it’s hard to imagine a lot of his work without him. Before he became a Covid-19 denier (sigh) Agamben could be incisive on Schmitt. I’m very critical of Agamben in The State of Sovereignty, by the way, but that doesn’t mean I don’t respect his work tracing (to simplify) how Schmitt’s friend/enemy distinction is found throughout the Western political tradition, which he frames in terms of what he says is Aristotle’s—he took this from Hannah Arendt, who mentions it in a footnote in The Human Condition—differentiation between bios (civic life) and zôê (bare life). In other words, if you think Schmitt is fascist, you should meet the entire Western tradition. (There’s a reason I titled my chapter in terms of Agamben’s “hyperbole”).

4. The Norms Approach

You know that discussion of Trump busting out of norms? In the media, it’s been a cliché since 2016 and little explained. But there’s a real theoretical pedigree to it. In the 1920s, as the Weimer republic went through its crises, Schmitt engaged in debates with Hans Kelsen (1881-1973), an Austrian legal philosopher and jurist. He is best known for his theory of "pure jurisprudence" or "legal positivism." This approach understands the law as a self-contained, hierarchical system of norms, independent of morality, politics, or sociology. Kelsen agrees with Schmitt that politics and the law is not about ethical norms (obviously if your sovereign can’t be reasoned with or second-guessed, any such norms are out the window), but he was a staunch defender of constitutionalism, the rule of law, and parliamentary democracy—precisely the things Schmitt was attacking.

Kelsen countered that law was a system of norms, validated by a "basic norm" (Grundnorm) that grounded the entire legal system (so there’s even a theoretical basis to the claim that Trump is throwing out “basic norms”). He rejected Schmitt's emphasis on the exception, arguing that even emergency powers must be derived from the legal order itself. He saw law as a way to constrain political power, not as its expression. He rejected the idea that a sovereign could stand outside the legal system—after all, what is a “president” if there aren’t enumerated powers in the law and a constitution naming such a thing, or the taxes to pay for the executive police and military agencies (raised by a legislature), etc. In a manner like those born to privilege who think they got their success on their own, Kelsen argues the executive can’t exist without that wider framework.

5. Leo Strauss's Critique of Schmitt

Leo Strauss (1899-1973), a German-Jewish political philosopher who emigrated to the United States, engaged deeply with Schmitt's work, most notably in his "Notes on Carl Schmitt, The Concept of the Political" (originally written in 1932). Strauss, best known for his “esoteric” reading of political theory, gives a complex critique of Schmitt (he seems to be quite exoteric himself in these writings), but here are some key elements:

The need to take Schmitt seriously: Strauss recognized Schmitt as offering a powerful critique of liberalism. He didn't dismiss Schmitt out of hand, as many others did.

The problem of liberalism's "groundlessness": Strauss agreed with Schmitt's diagnosis that modern liberalism had become detached from any firm grounding in a conception of the good life or human nature. (Of course, Schmitt’s doesn’t have that either!) Liberalism, in Strauss's view, had become overly focused on procedure and neutrality, leaving it vulnerable to attack. In short, liberalism is weak and sick.

Schmitt's "moralism": Despite critiquing liberalism, Strauss argued that Schmitt was ultimately a "liberal" himself. By this, Strauss meant that Schmitt's focus on the decision of the sovereign, and his emphasis on the intensity of the friend/enemy distinction, still relied on a kind of liberal moralism. Schmitt, according to Strauss, didn't offer a true alternative to liberalism, but rather a radicalization of some of its own premises, not least his focus on the procedures of sovereignty. (This is as clear as I can make Strauss on Schmitt on this point—it’s odd and half-hearted.)

The need for a return to classical political philosophy: Strauss's ultimate response to Schmitt (and to the crisis of modernity in general) was a call for a return to classical political philosophy, particularly the thought of Plato and Aristotle. He believed that the ancients offered a more robust understanding of human nature and the political good, which could provide a firmer foundation for political order than modern liberalism.

Strauss’s critique of Schmitt, then, is that he didn’t go far enough.

The Sovereign Con

There are many other lines of critique of Schmitt—but in light of this Substack, I thought I would revisit three quotes I use in the The State of Sovereignty’s introduction, which, taken together, expose the core fraud at the heart of sovereigntist claims—what we might call, bluntly, the "sovereign con."

Here’s Hannah Arendt in her book Between Past and Future:

The famous sovereignty of political bodies has always been an illusion, which, moreover, can be maintained only by the instruments of violence, that is, with essentially nonpolitical means.

Arendt cuts to the heart of the matter: the supposed absolute power of the sovereign is a mirage. It's not a natural or inherent quality, but a carefully constructed fiction, propped up by force. That’s not to say “might isn’t right” isn’t convincing—a gun to your head does tend to concentrate the mind. But true political power, for Arendt, emerges from collective action and deliberation—the messy, often contentious, but ultimately human process of building a shared world. The sovereign, in contrast, relies on the threat of violence, a fundamentally anti-political tool, to enforce obedience. This reliance reveals the fragility of the sovereign's claim: if power must be enforced, it is not truly sovereign—it’s not so damn exception to the political order as it would have you believe.

The second is from Jacques Derrida in an early 2000s lecture (collected in The Beast and the Sovereign, V. 1):

The point is, as these fables themselves show, that the essence of political force and power, where that power makes the law, where it gives itself right, where it appropriates legitimate violence and legitimates its own arbitrary violence—this unchaining and enchaining of power passes via the fable, i.e., speech that is both fictional and performative . . . power is itself an effect of fable, fiction, and fictive speech.

Derrida highlights how sovereignty isn't a thing to be possessed, but a performance to be enacted. The sovereign's authority isn't derived from some higher law or inherent right, but from the very act of claiming that authority – from the "fictive speech" that constitutes the sovereign as sovereign. The sovereign's pronouncements, like the pronouncements of a character, create the reality they describe. This is the "performative" aspect of sovereignty: the sovereign becomes sovereign by saying they are, and by having that claim accepted (or at least, not effectively challenged). The "arbitrary violence" is thus "legitimated" through narrative – through the construction of a "fable" of sovereign authority—hence why kings and tyrants surround themselves with so many ecomiums to their glory (it’s not accidental), a point that Sharon ♨️🇨🇦 @sharonk.bsky.social has been making continuously:

Now, while a gun to your head is pretty convincing, we don’t need to take Schmittianism and all the ad hoc claims in recent weeks by Trumpists of Constitutional powers and gaslighting seriously—the force behind them is serious, everything else is part of the con. Any reader of Alice and Wonderland knows this:

“When I use a word,” Humpty Dumpty said in rather a scornful tone, “it means just what I choose it to mean—neither more nor less.” “The question is,” said Alice, “whether you can make words mean different things.” “The question is,” said Humpty Dumpty, “which is to be master—that’s all.”

So now we come not just to the con of it all, but also to what so many have felt over the last several weeks (and why those who engage too much with the Schmittians like it’s a debate clearly don’t get it), as laws and precedent seem to take on whatever meaning the Trump apologists need in the moment. In the above, Humpty Dumpty declares his own definitions, unbound by any external constraint. Alice's sensible question—can you simply make words mean whatever you want?—is brushed aside. For Humpty Dumpty (and for Schmitt's sovereign), the only relevant question is who has the power to enforce their definitions. This is the essence of the "sovereign con": the claim to absolute, self-justifying authority, based on nothing more than the will to power and the ability to make that will stick, through violence or its threat.

That this is true doesn’t make it any better: after all, when the con is in charge, there are no cops to call. But Arendt and Derrida’s claims aren’t airy-headed nonsense (oh don’t you know, it’s just a performance?)—rather, they demonstrate that every such regime, no matter how “exceptional” and powerful, depicts itself as not needing your acquiescence even as they require it. (This is what connects the above to her writings on Eichmann, which I discussed yesterday.) The con works not by persuasion but by getting you to see what’s happening as the automatic run of things—nothing to be done. In the—god help us—weeks and months and years ahead, no one is coming to save us. The challenge, then, is to refuse the sovereign's self-serving definitions, to challenge the fables that prop up their power, and to insist on a politics grounded in democratic justice, not the illusion of absolute command.

So…what you’re saying is that Schmittian is pretty Shittian then :)

Thank you for this piece. It’s good to finally get to the bottom line of what’s been happening —where the foundation of it all originated.

I already knew that no one was coming to save us, but convincing others has been extremely difficult. Too many stuck in the liberal bubble as I learned well after October 7, 2023.